👑

São Bento* from Nursia

THE SECRET OF SÃO BENTO

the great hunt for the saint in capoeira

The ABC

480 - Born on March 24 in Norcia, Umbria, Kingdom of Italy, along with his twin sister Scholastica.

49? - Moved to Rome to study rhetoric and philosophy.

500 - Withdrew to Enfide (now Affile, in Subiaco, in the region of Lazio).

503 - Received a large number of disciples and founded twelve small monasteries.

516 - Wrote the Rule of Saint Benedict.

529-Because of the envy of the priest Florentius, he moved to Monte Cassino.

530 - Founded the monastery at Monte Cassino. This would become the foundation of the expansion of the Benedictine Order.

534 - Started writing the Regula Monasteriorum (Rule of Monasteries).

547 - Escolástica passed away on February 10th. Bento died on March 21 in Monte Cassino.

NB! The day of São Bento is celebrated on the 11th of July.

* In this study São Bento = Saint Benedict and São Benedito, the other saint, is not translated.

Images

Now the capoeira asks himself: why are there so many São Bentos in capoeira? Many more than other saints. This is the secret of São Bento!

THE SECRET OF SÃO BENTO

the great hunt for the saint in capoeira

by Sven Pruul

AD 2015

(trans. by Google)

-

TABLE OF CONTENTS

-Introduction

CHAPTER 1 - São Bento - Omolu - São Benedito

CHAPTER 2 - Places associated with Saint Benedict

CHAPTER 3 - São Bento and Capoeira

CHAPTER 4 - Songs of São Bento, Omolu and São Benedito

CHAPTER 5 - Medal of Saint Benedict and the Dobrão

CHAPTER 6 - The rhythms of São Bento and the berimbau

Summary -

+

Introduction

Those who have been practicing capoeira for some time must have noticed that the word par São Bento appears frequently in our songs or capoeira terminology. São Bento, of course, means São Bento, a Catholic saint, in Portuguese. A quick internet search gives us an insight into the life and (miraculous) works of the truly devoted Catholic Benedict of Nursia, Italy who lived in the 5th to 6th centuries. In this work, in addition to Saint Benedict, I will highlight two other relevant names – Omolu and Saint Benedict. Omolu is one of the few orixás of Afro-Brazilian candomblé syncretized with São Benedito. São Benedito, on the other hand, was a black cleric who lived in the 16th century and was later canonized, and there is reason to distinguish him from São Bento (see CHAPTER 1).

It is known that sanctuaries were built with saints and precisely these could reveal something about the influence of São Bento in capoeira (see CHAPTER 2).

But what has linked São Bento so strongly to capoeira throughout history? At this point, I must admit that I'm not the only one who has been concerned about these issues. However, the discussions so far are not enough to understand the impact of São Bento. I had the following questions: Were the capoeiristas of the 18th and 19th centuries Benedictine? Perhaps some of the old masters were followers of Saint Benedict? Why isn't São Bento talked about more? (see CHAPTER 3)

Dozens of songs mention Saint Benedict, certainly more often than other saints. Omolu appears less frequently, but for a better coverage of the theme of the work, I will cite the songs that I remember or researched, both about him and about São Benedito. Maybe there is a hint in the songs? Where do the oldest songs of São Bento come from? Are there songs dedicated to São Bento in other parts of Afroculture today: samba, jongo or coco, which capoeira songs are more inspired by? (see CHAPTER 4)

It is said that capoeiristas used to play the berimbau with the São Bento medallion because it was a good size. This is already a tangible link between capoeira and São Bento. So, in addition to trying to find a medallion, I'll describe how it was used in the past and today (see CHAPTER 5).

The São Bento is also strongly represented in the names of the rhythms of the berimbau, whose variety I will try to clarify. What do the suffixes Pequeno and Grande in the name São Bento refer to? (see CHAPTER 6)

Here it is worth noting that, curiously, the name São Bento does not appear in the names of capoeira movements.

I came across a saying that says that capoeira is the game of São Bento – the game of São Bento. May the following pages be a game of seeking answers to the mystery of São Bento (who, where and why?) - a great hunt for capoeira saints.

-

+

CHAPTER 1 - São Bento - Omolu - São Benedito

1.1 Saint Benedict in the Catholic faith

Saint Benedict is a saint of the Catholic Church. He was declared a saint in 1220. The Italian monk Benediktus lived between 480 and 547 and founded the oldest and one of the largest religious monastic orders in the world - the Benedictine order, which has monasteries and churches throughout the world. There were no Benedictine monasteries in Estonia, but the nuns of the order Birgitta are guided by Benedict's instructions for monastic life, which have been adapted for nuns and date back to the year 529, when Benedict founded the monastery of Monte Cassino.

Saint Bento is mostly depicted as an old man with a beard (Image 1), who holds a cross in one hand and a book with instructions for monastic life in the other.

Image 1. Statue of St Benedict in Ealing St, London. Catholic Church of the Monastery of São Benedito. Private Collection But there are also portraits of him when he was younger (Image 2).

Image 2. Saint Benedict from the wall of the church of San Benedetto in Piscinula in Rome. Church brochure Saint Benedict is addressed in the Catholic Church with the following image-filled prayer, a litany:

Lord, have mercy Lord, have mercy.

Christ, mercy Christ, mercy.

Lord, have mercy Lord, have mercy.

Christ, mercy Christ, mercy.

Christ, hear us Christ, hear us.

Christ, answer us Christ, answer us.

God, Father in heaven, have mercy on us.

Son, Redeemer of the world, have mercy on us.

God, Holy Spirit, have mercy on us.

Holy Trinity, One God, have mercy on us.

Saint Mary, pray for us.

Glory of the Patriarchs, pray for us.

Compiler of the Holy Rule, pray for us.

Portrait of all virtues, pray for us.

Example of Perfection, pray for us.

Pearl of Holiness, pray for us.

Sun that shines in the Church of Christ, pray for us.

Star that shines in the house of God, pray for us.

Inspirer of All Saints, pray for us.

Seraphim of fire, pray for us.

Transformed cherub, pray for us.

Author of wonderful things, pray for us.

Master of demons, pray for us.

Model of the Cenobites, pray for us.

Destroyer of idols, pray for us.

Dignity of confessors of the faith, pray for us.

Consolator of souls, pray for us.

Help in tribulations, pray for us.

Signified Holy Father, pray for us.

Lamb of God, who take away the sins of the world, forgive us Lord!

Lamb of God, who take away the sins of the world, answer us Lord!

Lamb of God, who take away the sins of the world, have mercy on us, Lord!

We take refuge under your protection, Holy Our Blessed Father.

Do not despise our needs and tribulations.

Help us in the fight against the evil enemy and, in the name of the Lord Jesus, help us eternal life.

V. He is encouraged by God.

R. He who, from heaven, defends all his children source .In the article Papa Bento XVI and capoeira São Bento, Miltinho Astronauta writes that the happy choice of the name of the [former] Pope - Bento (Bento) XVI - leads us almost naturally to the former capoeira São Bento source .

The 9 days of prayer source of Saint Benedict is a moment in the Catholic Church in which Saint Benedict is intensely venerated for 9 days.

To be canonized by the Catholic Church and the Pope, a follower of the faith must have performed several miracles in addition to meeting other criteria. In the case of Saint Benedict, this included bringing a boy back to life while praying for him, breaking the untouched poisoned chalice (it is said that the poisonous snake came out of it) and getting rid of the poisoned bread with the help of a crow that flew with it.

For comparison, we can take two miracles of Pope John Paul II. The Pope supposedly cured a woman of Parkinson's and another of an aneurysm.1.2 Omolu in Candomblé

[Saint Bento] was the patron saint of foresters, shepherds, and other forest walkers because he was a protector against snakes. The author of the article Senhor São Bento always thought that the constant references to snakes and their contortions, going to the ground, etc. refer to São Bento. In addition, it has syncretism with Omolu/Kingongo source .

Omolu or Obaluaiê (Image 3), the orixá (of death) of Candomblé, is syncretized with São Benedito (Taylor, 2005), the saint of good death, in the lamentation of diseases, cemeteries and infectious diseases. Omolu's face is covered because his face is deformed due to illness. Another saint associated with Omolu is São Lázaro [São Lázaro], whose protectors are the sick, mainly lepers and plague victims, as well as victims of gwar. Obaluaiê, in turn, is associated with São Roque, who protects plague patients source .

Omolu (Yoruba k. omu – sharp + oolu – makes holes) can bring diseases, but also take them away. Her devotees attribute miraculous healings to her and prepare popcorn called deburu or doburu as gifts. Omolu's colors are red, black and white. Omolu's day of worship is Monday, and in many temples it is very important.

In turn, there is not just one candomblé, but more than ten - several African nations in Brazil have their own form of candomblé. The caboclo candomblé, or form of candomblé resulting from the mixture of Nagô, Jeje and indigenous religions, has as its highlight the Santo da Cobra, or Cobra Cauã, which is associated with São Bento, an interesting combination of Omolu and Dã (snake). There is also a caboclo candomblé song (see 4.7 Cantigas de não capoeira mentioning São Bento, nº 1)) that reveals an interesting Gêge-Nagô-Banto-Caboclo-Catholic syncretism.

Image 3. Omolu no Cajueiro, school of capoeira M Dorado, shown in the middle and larger than the other orixás. Private Collection Omolu's dance is called opanije (Image 4).

Image 4. Dance of Omolu. Photo from the internet 1.3 São Benedito

Like São Bento, São Benedito source is also a saint of the Catholic Church, and because of the similar names, care must be taken not to confuse them. São Benedito lived in the years 1526-1589 and was of African descent. There are few references to him in Capoeira songs - those few are listed in Chapter 4.

De Brito writes in São Bento, Bentinho the African and Benedito the African and Bento the charioteer that, like São Bento, São Benedito is credited with the ability to resist snake venom. It is said that when the image of Saint Benedict was taken to a dying person, he, seeing the image, spit out the snake that had poisoned his heart. In the Afro-Brazilian religion, patuás are used as protection against snake venom and betrayal, an activity that is also common among capoeiristas today.

The black Saint Benedict is a glorified saint in Brazilian jongo.

-

+

CHAPTER 2 - Places associated with Saint Benedict

The first Benedictines to settle in Brazil came from Portugal in 1581. They founded the following monasteries: São Sebastião in Bahia (1581/2?); Virgin of Montserrat in Rio de Janeiro (1589), São Bento in Olinda (1640); Feast of the Assumption of [Mary] source in São Paulo (1640); Santa Madre in Paraíba (1641); Santa Madre in Brotas (1650), Santa Madre near Bahia (1658) and four monasteries dependent on São Paulo source .

When I visited Brazil at the end of 2012, I unfortunately found no Benedictine church-monasteries, although I have been to the doors several times. However, songs about São Bento accompanied me on my way in London, Rio de Janeiro, São Paulo and Salvador.

At the beginning of the trip, I stopped in London, where I managed to participate in the Urban Ritual, an open capoeira circle organized in Charlie Wrights bar by the English master of capoeira Angola, Fantasma. I've heard a little-known song there about São Bento (see CHAPTER 4, 4.5 Corridos and blocks of São Bento, nº 1). While going to train at M Carlão's school in the Botafogo neighborhood of Rio de Janeiro, the training sessions were also accompanied by some songs about São Bento that played on the CD player. In São Paulo and Salvador, the songs also reached my ears in the circles.

In Salvador, I happened to attend a celebration (although not Catholic) in front of the oldest Benedictine church in Brazil source , built in 1582 (Image 5).

Image 5. Church of São Bento in Salvador. Photo from the internet According to the Brazilian researcher Nina Rodrigues, in the beginning of the 19th century, blacks of Nagô origin (Angola) gathered in Salvador precisely on the slope of São Bento (Image 6).

Image 6. Dois de Julho (Bahia Independence Day, July 2, 1823) at Praça São Bento, with the church in the background. Photo from the internet In São Paulo, I found the Monastery of São Bento source (Image 7), founded in 1598.

Image 7. Monastery of São Bento in São Paulo. Personal collection In Rio de Janeiro, the Benedictine monastery source (Image 8) was built in 1590 by monks who arrived from Salvador, Bahia, at the request of the inhabitants of the newly founded city of São Sebastião.

Image 8. Monastery of São Bento in Rio de Janeiro. Photo from the internet Travelling through France and Italy in 2013, I drew up a plan to make up for my mistakes in Brazil in 2012 and look for traces of the Benedictine ancestor in Europe. Unfortunately there was no trace of what I was looking for in a Bordeaux church with possible Benedictine connections.

In the same year my preparation continued to be weak, because in Rome, as it turned out later, I was a few hours from Monte Cassino source - the monastery founded in 529 and in which Saint Benedict personally lived (Image 9).

Image 9. Monastery of Monte Cassino in Italy. Photo from the internet However, I went to a small but important Benedictine church located in Rome. It's called San Benedetto in Piscinula source (Image 10) to bless the acquired medallions (see CHAPTER 5).

Image 10. Church of San Benedetto in Piscinula in Rome. Personal collection In this church there is also a room (Image 11) in which the saint lived for some time while studying in Rome.

Image 11. The room in the church of San Benedetto where Saint Benedict lived. Personal collection In 2014 I went to the church of the Catholic monastery of S. Bento in Ealing London (Image 12), where the Benedictines have been active since 1896.

Image 12. Church of São Bento in London. Personal collection CHAPTER 6 reveals another historically important São Bento church in Brazil, which is currently in ruins (Image 13). It is located in the city of São Bento, in the state of Alagoas.

Image 13. Ruins of the Church of São Bento in São Bento. Photo from the internet -

+

CHAPTER 3 - São Bento and Capoeira

The capoeirista Felipe, nicknamed Salsicha, refers to the capoeira stories of São Bento and capoeira in the article, where, in comparison with the snake of some malicious capoeira comrade, we ask for protection from São Bento, because he became known as a saint who protects us from any kind of poisoning, including snakebite. He is also a saint whose life was closer to nature and animals. São Bento is also treated as the defender of capoeira. The ancient masters who laid the foundations of capoeira were all devotees of São Bento source .

However, to reach the full extent of St. Benedict's influence, we have to start further back, from the earliest days of slavery. The first black slaves were brought to Brazil in 1538. By the 17th century, it had reached the point where 44,000 were imported annually. According to the first reliable census in 1798, there were 1,582,000 slaves and 406,000 free blacks living in Brazil, while the total population was 3,250,000 (Mannix, D. P., Cowley, M., 1988. Black cargoes).

According to one version, when black Angolans arrived in Bahia, they brought with them a dance called cungú, which served to teach them how to fight. Over time, Cungú became Mandinga and São Bento (Camille Adorno, 2017. Arte da Capoeira).

The Christianization of Brazil, which began in the mid-16th century, was initiated by the Jesuits, after whom the Franciscans came, and after them the Benedictines. Jesuits often gathered natives into communes, where natives worked and converted to Christianity source . The Benedictines and Carmelites took over many of the Jesuit responsibilities after the Jesuits came into conflict with the Portuguese crown and were subsequently expelled from Brazil (Johnson, Elizabeth, 2008. Ora Et Labora: Labor Transitions on Benedictine and Carmelite Properties in Colonial Sao Paulo) .

How many slaves did the monks of São Bento have [at the end of the 18th century]? More than a thousand. There were believers who left behind so many slaves when they died that, when they were turned into money, they could be used to pay for beautifying temples or worshiping cults.

It wasn't just the Carmelite priests who stood out the most when it came to disorder. The quarrelsome ones were also the priests of São Bento (Edmundo, Luís, 2000. Rio de Janeiro in the time of the viceroys: 1763 - 1808).

Koster (1816, Travels in Brazil) writes that Africans imported from Angola are baptized immediately before leaving their lands and, upon arriving in Brazil, learn the doctrines of the church and the duties of the faith into which they entered. They wear the insignia of the royal crown on their chests, signifying that they have gone through the ceremony of baptism and that their royal duty has been paid for. Slaves imported from other parts of the African coast arrive in Brazil without baptism, and before the Christianization ceremony takes place, they must know certain prayers, which the master is given two years to teach, after which he is obliged to bring the slave to church. parochial.

The policy [Christianization] consisted mainly in allowing the blacks to retain, along with European customs and Catholic rites and doctrines, the forms and accessories of their African culture and mythology. João Ribeiro highlights the fact that Christianity in Brazil made some concessions to slaves in its rites, which included black saints such as São Benedito and Nossa Senhora do Bonfim, who became patron saints of black societies (Ribeiro, João, 1900. História do Brasil ).

The kings of the Brazilian Congo venerate Our Lady of the Rosary and dress in white men's clothes. With their subjects they dance according to the custom of the country, but at these festivals black Africans from other nations, black creoles and mulattos, all who dance in the same way, are admitted; these dances are today both Brazilian and African folk dances (Koster 1816).

The spread of slaves depended almost entirely on the movement of their masters, who in turn were influenced by the discovery of mineral resources or the appreciation of new plant crops. The first to influence the dispersal of slaves across Brazil was the cultivation of sugar cane, which began to be practiced in the states of Bahia and Pernambuco.

Henry Koster, an Englishman who managed a farm in Pernambuco and had ample opportunity to observe the Benedictine farm in Jaguaripe, only praised its methods and results (Schwartz, Stuart B., 1982. The plantations of St. Benedict: The benedictine sugar mills of colonial Brazil). Koster, who traveled through Brazil in the early 19th century, wrote that monks live permanently in Benedictine properties. Slaves treat their masters with great camaraderie; they honor only the abbot, whom they consider the representative of the Saint.

Koster writes that: one of these old men, who was still vigorous enough to be frequently in a state of drunkenness, and would walk a considerable distance to get something to drink, made it a habit to visit me for that purpose. He told me that he and his companions were not the slaves of the monks, but of Saint Benedict himself, and that consequently the monks were only agents of their master, administering the saint's goods in this world. I asked some other slaves about this and concluded that such an opinion prevailed among them (idem).

All slaves in Brazil follow the religion of their masters [..] (idem).

Capoeira is not mentioned in known writings until the 18th century in Rio de Janeiro. However, we can think that the initial transport of slaves to the northeastern states may have given rise to the precursor of capoeira. This is probably also due to the fact that the oldest known capoeira masters are from Bahia.

We can also conclude that many, if not most, of capoeira's predecessors were slaves brought from Angola to Bahia or their descendants who belonged to the Benedictines and were thus converted. These slaves had to be more mobile than the slaves who worked in the fields, they had to have more freedom to practice their amusements in hidden places.

In favor of the religious slaves' version is the fact that in capoeira today, especially capoeira Angola, which has a longer tradition, religion plays a greater role than many capoeiristas admit: long introductory litanies of litanies are sung before the beginning of the circle, the sign of the cross is made, chants invoke God and various saints (Saint Bento, Santa Maria, Santo Antônio and others). One might think that formerly such customs were more significant. Today, songs addressed to God and saints are taken for granted, St. Benedict is probably not addressed in any significant way, but there are probably many exceptions. So far, however, this saint is the most popular among capoeiristas - this will be confirmed again in CHAPTER 4.

If slaves were worshipers of Saint Benedict, what would that look like? He was probably guided in many ways by religious obligations: going to church on Sunday and celebrating days related to saints. It was customary to dress in white to go to church, which was good for wearing afterwards and trying to stay clean when playing, including capoeira circles.

It is not difficult to imagine that when the berimbau was introduced, the name of the saint - São Bento - was added to its rhythms (see CHAPTER 6). Here again, Benedictine slaves were supposed to be at the forefront, adapting songs that mention Saint Benedict of the prayers and were supposed to adopt his medallion at some point (see CHAPTER 5). At some point, capoeira from São Bento may have been influenced in such a way that capoeira came to be called the game of São Bento - in the 1953 article Angola, São Bento ou Regional we find that the people from São Paulo are taught to fight according to the prescription of the Capoeira de São Bento, who puts his hand on the client, is effective and courageous (Ultima Hora, SP, 28/11/1953: Berimbau and capoeira in the editorial office of „Ultima Hora“ – they refuse to return to Bahia without teaching the paulista to fight).

-

+

CHAPTER 4 - Songs of São Bento, Omolu and São Benedito

4.1 Background

In the article Papa Bento XVI and capoeira São Bento, Miltinho Astronauta writes that M Gerson Quadrado asks almost in a reproachful tone at the beginning of his capoeira Angola CD "Encanto banto num recanto da Ilha":

“Do you know São Bento?

Don't you know São Bento?

Jeesus! Are you capoeira and don't know São Bento?..” sourceIf you interpret a little the songs sung in capoeira, you will see a clear connection between São Bento and the snake - São Bento is supposed to protect us from snakes. Miracles are attributed to this saint, where he escaped poisoning.

In "São Bento, Bentinho the African and Benedito the African and Bento the charioteer" it gradually becomes clear that just as the corridos can be Benedito the African (M Pastinha's master); the African Saint Benedict; the African Bentinho (master of M Bimba); by evoking Negro Bento (master of M Bobó) and São Bento, the song may try to reach other ancient and well-known powerful mestres [..] [Celso de Brito, 2011. The mobilization of religious symbols in capoeira: syncretisoms and anti-syncretismos. ]

W. Rego writes in his 1968 book that chants 8, 11, 35, 114, 122, 138 invoke the protection of São Bento against snakebites, a tradition that spread throughout the country. He well remembers, as a boy, constantly hearing "stuck in the strings of St. Benedict" three times when a venomous creature was seen passing by so that it could be pinned down and killed. Oswaldo Cabral writes about a series of prayers of Saint Benedict against snakes and venomous animals - they are of a preventive or curative nature.

In capoeira songs, the invocation of São Bento has a preventive character. The prayer published by Oswaldo Cabral has a preventive character, which says the following:

My glorious Saint Benedict, who rises above the altar, come down from there with your holy water and bless the places where I come, drive away snakes and poisonous creatures: so that they have no teeth to kill me, nor eyes to see me. Help me, Saint Benedict, Son, help my Guardian Angel and help the Virgin Mary. Amen. [W. Rego, 1968. p 244-246.]It could be argued that prayers for protection are often presented in the form of a song.

According to my 2009 research source is the snake, which is most often used in capoeira songs. We can imagine that it is necessary to remove nervousness or fear of an opponent or “snake”.

In other words, says M Nestor, of all the animals, the snake is the most exalted in capoeira songs, perhaps because of its flexibility and for being fast, precise, treacherous and deadly when it attacks. [M Nestor, 2007. The little capoeira book.]

Compared to Santa Maria [Holy Mother (of God) or Oba of candomblé] and Santo Antônio [Saint Antônio or Ogum of candomblé], São Bento [Omolu of candomblé] is probably the one that is most sung about. The high ranking of Saint Mary as one of the most sacred figures of the Catholic Church among the most common references in songs is understandable, but in the case of Saint Benedict, the increased attention is appropriate.

4.2 Litany of Saint Benedict

1) Prayer to Saint Benedict - the medallion prayer (ladainha adp. by M Guará), see also about the medallion in CHAPTER 5

Iê!

Na oracão de S ã o B e n t o [words with intervals here and later from the author of the work]

A cruz sagrada é minha luz

Não seja o dragão meu guia

Em nome da santa cruz

Sai pra lá coisa ruim

Não me aconcelhe mal

Isso que tu me oferece (ai ai ai)

Nunca foi coisa pra mim

Beba tu do seu veneno (ai meu Deus)

Deixe-me viver em paz

Ai meu Deus senhor S ã o B e n t o

Nós livre de todo mal

Nessa oração te peço (ai meu Deus)

Proteção celestial

Camaradinha!Comment: This litany is an unmistakable prayer to Saint Benedict in the form of a song.

4.3 Litany mentioning Saint Benedict

1) Orixás da Bahia - M Bola Sete

Iê!

Xangô rei de Oyó source

O Exu é mensageiro

O m o l u Senhor S ã o B e n t o

Oxóssi santo guerreiro

Iansã das tempestades

Janaína rainha do mar

Nanã Iyabá source Senhora

Mãe de todos os Orixás

Ogum o Deus da guerra

Oxalá santo de fé k

Olurum o rei supremo

O Senhor do candombléComment: This litany mentions Saint Bento as one of the syncretized orixás of candomblé.

2) I'm going to read the alphabet - M Pastinha

Eu vou le o B-A-BA

O B-A-BA do berimbau

A cabaça e o caxixi

E um pedaço de pau

A moeda e o arame

Está aí um berimbau

Berimbau é um instrumento

Tocado de uma corda só

Pra tocar S ã o B e n t o G r a n d e

Toca Angola em tom maior

Agora acabei de crer

Berimbau é o maior

Camara!Commentary: The name São Bento is used here in the name of the rhythm of the berimbau.

3) Litany – M Adó (CD Na trilha da nossa cultura)

Era jogo[?] de S ã o B e n t o

E agora Santa Mariaa

Iúna, jogo de dentro

E vem lá cavalaria

Berimbau tocou S ã o B e n t o

E eu posso lhe provar

Meu mestre entrou de sola

No crioulo ..

Apesar de muito raro

Nunca levei prejuízo

Era discípulo de aço

Nunca viu gato pretinho

Mas um dia um gato preto

Na ladeira da Lapinha

Era um dia[?] que o malvado

E era meu mestre Pastinha

Camaradinha!Comment: Ladainha difficult to decipher, but it refers to the capoeira game called São Bento.

4) Let the life happen - M Virgílio de Ilhéus

Deixa tudo acontecer

Para ver o que vai dar

Querem tomar meu espaço

Não sei onde eu vou parar

Eu tenho meu Jesus Cristo

Nossa Senhora no altar

Vou pedir ao S ã o B e n t o G r a n d e

Pra ele nós ajudar

Tira esse olhos grossos

Que querem na atrapalhar

[..]Commentary: A reference to São Bento Grande (!) which, according to the logic of the Portuguese language, would also imply the existence of a São Bento Pequeno.

5) Long live God in the heights - M Virgílio de Ilhéus

Iê!

Oh viva Deus nas alturas

Oh viva o mundo inteiro

No céu vai só quem merece

Na terra vale o dinheiro

Oh viva meu berimbau

Que me livrou do cativeiro

Vou pedir a todos os santos

Para eles nós ajudar

Abençoem aqui esta roda

E a todos que estão

Salve Bimba e Pastinha

Deus lhes bote em bom lugar

Valei-me meu S ã o B e n t o

Valei-me meu São José

Deus me livre desta cobra

Para não morder meu pé

Camaradinha!Commentary: An apparent prayer to St. Benedict for protection.

4.4 Litany where Omolu is mentioned

1) Atôtô [shout to Omolu in Yoruba] – M Dorado

Iê!

Atôtô / Silence!

Atôtô Obaluaiê / Silence for Obaluaiê!

Atôtô O m o l u Olukê / The son of the Lord is the Lord who calls

A Jiberu

A Ji beru Sapada / We wake up and run in fear

Peço licença e proteção

A meu Orixa

A Jiberu

A Ji beru Sapada / We wake up and run in fear

Peço licença e proteção

Para vadiar

Atôtô

Atôtô Obaluaiê

Atôtô Omolu Olukê

Atôtô Obaluaiê

Atôtô Baba

Atôtô Obaluaiê

O m o l u é orixaCommentary: Salute to Omolu, sometimes syncretized with São Bento.

2) Syncretism - Paulo César Pinheiro (ladainha adp. M Forró)

O negro religioso

Dentro de casa tem seu gongá

Porém desde o cativeiro

Mudou de nome o seu orixa

E assim dona Janaína

É Nossa Senhora da Conceição

Oxum é das Candeias

Oxossi é São Sebastião

São Lazaro é O m o l u

Como Santa Barbara é Iansã

São Roque é Obaluaiê

São Jorge é Ogum

Santa Ana é Nanã

E assim São Bartolomeu é Oxumarê

São Pedro é Xangô

Oba é Joana d'Arque

Pai Oxalá Nosso Senhor do BonfimComment: Here Omolu is syncretized with Saint Lazarus.

4.5 Corridors and quadras of São Bento

1) Eh eh ah

Eh eh oh

São Bento me chama

São Bento chamou [Heard in the roda of Urban Ritual on 11.04.2012]:,: [The symbol here and below represents the chorus] Eh eh ah

Eh eh oh

São Bento me chama

São Bento chamou :,:Commentary: Saint Benedict must be calling me under his protection. It is also possible that capoeira, or the game of São Bento, is calling me.

2) Ai ai ai

São Bento me chama :,: Ai ai ai :,:Comment: See previous.

3) I'm going to play São Bento - Prof. Esquilo

Quando eu avistei a roda

Ouvi berimbau tocar

Capoeira está jogando

São Bento mandou chamarEu vou jogar São Bento

Olha o jogo de fora, olha o jogo de dentro

:,: Eu vou jogar São Bento :,:Eu vou levar meu Barravento [berimbau rhythm]

:,: Eu vou jogar São Bento :,:Eu vou cantar o meu lamento

:,: Eu vou jogar São Bento :,:Olha o jogo de fora, olha o jogo de dentro

:,: Eu vou jogar São Bento :,:Cuidado com a meia-lua

Olha a armada ligeira

Olha a rabo-de-arraia

E o tombo da ladeiraMas antes de entrar na roda

Faça uma oração

Pedindo para São Bento

Dar a sua proteçãoComment: A reference to São Bento as a game and as a saint.

4.1) Valha me Deus Sinho São Bento

Vou jogar meu barravento

:,: Valha me Deus Sinho São Bento :,:Comment: Protection is requested here.

4.2) Valha-me Deus Sinho São Bento - M Tucano Preto

Valha-me Deus sinho São BentoComment: See previous.

5) São Bento proteja esse jogo

São Bento proteja esse jogo

São Bento me deixa jogar

São Bento proteja esse jogo

Que a capoeira agora vai rolar:,: São Bento proteja esse jogo

São Bento me deixa jogar :,:Esse menino me convidou

Para uma festa e eu vou lá

Capoeira eu jogo aqui

Jogo em qualquer lugar:,: São Bento proteja esse jogo

São Bento me deixa jogar :,:São Bento proteja esse jogo

Que a capoeira agora vai rolarEsse menino jogo comigo

Jogou comigo tá querendo me pegar

Já me deu martelo já me deu rasteira

Entrei no contragolpe e joguei pra lá

São Bento proteja esse jogo

São Bento me deixa jogarEsse menino foi meu aluno

Foi meu aluno tá querendo me enganar

Tem mandinga tem balanço no gingado dele

É cobra criada não pode me picar:,: São Bento proteja esse jogo

São Bento me deixa jogar :,:São Bento proteja esse jogo

Que a capoeira agora vai rolar sourceComment: See previous.

6) São Bento proteja capoeira e a mim source

Comment: See previous.

7) São Bento proteja a capoeira source

Comment: See previous.

8) São Bento calls me - Coala

São Bento me chama

São Bento me quer

São Bento proteja

Quem capoeira é sourceComment: Once again, it is possible that capoeira, or the game of São Bento, is calling me, but it seems more like a saint calling.

9) Aloanguê, São Bento ta me chamando, Aloanguê [Manuel Querino, 1916 source , also on M Ananias' CD, 2004

Comment: See previous.

10) Mas [cadê] seu Caitão? :,: São Bento :,: [CD by M Ananias, 2004]

Comment: Game or saint?

11) Tira a cobra do caminho meu senhor São Bento

Senhor São Bento, senhor São Bento

:,: Tira a cobra do caminho meu senhor São Bento :,:

Deus me livre dessa cobra, desse bicho peçonhento elukast

:,: Tira a cobra do caminho meu senhor São Bento :,: sourceCommentary: Prayer to Saint Benedict to ward off danger, to protect.

12) Essa cobra é venenosa, tá querendo me morder (2x)

Vou chamar senhor São Bento para ele me valher

Oh São Bento me ajude, me livre do mal

A cobra é venenosa o veneno é mortal

:,: São Bento me ajude, me livre do mal :,:

Essa é cobra é danada, o veneno é fatal

:,: São Bento me ajude, me livre do mal :,: [CD 3 by M Jogo de Dentro, 2007]Comment: See previous.

13.1) Queria ir

Mas agora não vou mais

No caminho me apareceu

Uma cobra de corais

E a cobra lhe morde

:,: Senhor São Bento :,:Oh, jibóia não tem veneno

Jararaca é respeitada

Cobra mata na cabeça

Não fere deixa na estrada

Moço não fere esta cobra

Mais tarde vai lhe picar

Cobra mata na cabeça

Oh, não mata em outro lugar

Oh, mas, a cobra lhe morde

:,: Senhor São Bento :,:

A cobra é danada

:,: Senhor São Bento :,:Comment: See previous.

13.2) Ia passando num caminho

Uma cobra me mordeu

Meu veneno era mais forte

Essa cobra que morreu

Olha a cobra, lhe morde

:,: Sinho São Bento :,:

Olha o bote da cobra

:,: Sinho São Bento :,:

Ela é venenosa

:,: Sinho São Bento :,: sourceComment: See previous.

14) Cobra mordeu São Bento, Caetano [W. Rego, 1968]

Comment: According to Carneiro (1937), this is a modification of the caboclo's candomblé song (see 4.7 Non-capoeira songs mentioning São Bento, nº 1)). There are no records of such a case - it is not known whether the snake that came out of the poison chalice when it broke could have bitten the saint.

15) Valha meu Deus valha meu Deus Virgem Maria

Essa agonia senhor São Bento, nessa roda, nesse dia sourceCommentary: Prayer of protection to Saint Benedict.

16.1) Misericórdia São Bento

Misericórdia São Bento

Buraco velho tem cobra dentro

:,: Misericórdia São Bento :,:Comment: See previous.

16.2) Misericórdia São Bento

Misericórdia São Bento

Essa cobra te morde São Bento

:,: Misericórdia São Bento :,:

Essa cobra te morde São Bento

:,: Misericórdia São Bento :,:

Essa cobra te morde São Bento

:,: Misericórdia São Bento :,:

Essa cobra te morde São Bento

Essa cobra te morde São Bento

Essa cobra te morde São Bento

:,: Misericórdia São Bento :,:

Essa cobra te morde São Bento [Spevnik3.doc]Comment: See previous.

17) Prayer of São Bento - M Oscar

São Bento se tocar na roda eu jogo

Se falar do santo eu rogo

Rezo e peço proteção

Sou negro se insistem

Em me chamar de escravo

No meu corpo sofrido e suado

São as marcas da escravidão

São marcas de todas as batalhas da vida

Vitórias e perdas sofridas

Não perco minha devoção

Carrego no peito

A medalha de São Bento

Pra me acudir do sofrimento

E me livrar da maldição:,: São Bento se tocar eu jogo

São Bento pro santo eu vou rezar

São Bento se tocar eu jogo

São Bento pro santo eu vou rezar :,: sourceComment: This story mentions a rhythm called Saint Benedict, a saint, and a medallion dedicated to him.

18) Game of Angola, game from inside - interpreted by M Roberval

Jogo de Angola, jogo de dentro

Meu berimbau vem de lá de São Bento

:,: Jogo de Angola, jogo de dentro :,:

Meu berimbau, ele toca São Bento

:,: Jogo de Angola, jogo de dentro :,:Comment: There is a reference here to São Bento as a place and as a rhythm. The reference to a place called São Bento is not frequent.

4.6 Non-capoeira songs of São Bento

1) Rhythm of São Bento Pequeno – Paulo César Pinheiro

:,: No coração contra o veneno

A proteção é São Bento pequeno

No coração contra o veneno

A proteção é São Bento pequeno :,:Numa roda de gente eu sou pacato

Numa briga de morte eu sou sereno

Arrodeio valente que nem gato

Estudando primeiro seu terreno

Camará mas depois que eu tomo tato

Essa briga de morte vira treino

Eu derrubo malandro mas não mato

Foi meu trato com São Bento pequeno:,: No coração contra o veneno

A proteção é São Bento pequeno

No coração contra o veneno

A proteção é São Bento pequeno :,:O crioulo me diz que eu sou mulato

O branquelo me diz que eu sou moreno

Tem quem diga que eu sou bicho do mato

Porque me fazem mau, mas eu não temo

Nem com furo de bala não me abato

Nem com corte de faca muito menos

Pois meu corpo eu fechei com um retrato

Da medalha de São Bento pequeno:,: No coração contra o veneno

A proteção é São Bento pequeno

No coração contra o veneno

A proteção é São Bento pequeno :,:Camará Capoeira eu sou de fato

Quando chamam bezouro, eu olho e asceno

Quem quer briga jamais deixo barato

Já começo com o pé no duodeno

Com meu Santo aprendi e sou grato

E ele foi protetor do nazareno

Hoje protege a mim com muito trato

Com respeito a meu São Bento pequeno:,: No coração contra o veneno

A proteção é São Bento pequeno

No coração contra o veneno

A proteção é São Bento pequeno :,:Commentary: It mentions São Bento Pequeno, which is the name of one of the rhythms of the berimbau, but it is still not clear what the difference between São Bento Grande and São Bento Pequeno should be.

2) Valha Deus, Sinho São Bento! source

Comment: Again, protection is requested.

3) Quando eu passo em tua porta

Teu pae sempre diz: São Bento

— Não sou cobra que te morda

Nem sou bicho peçonhento

(Minas.) [Mil quadras populares 1916, n 816]Commentary: Poetry from the early 20th century or earlier.

4) Glorioso São Bento

Meu glorioso São Bento

Meu Jesus de Nazaré

Oxala é nosso Pai

Valei aos filhos de fé! sourceComment: a prayer of Umbanda, Afro-Brazilian religion.

4.7 Non-capoeira songs that mention São Bento

1) São Bento ê ê São Bento ê á

Omolu Jesus Mariá

Eu venho de Aloanda

Jesus São Bento Jesus São Bento

No caminho de Aloanda

Jesus São Bento

Cobra mordeu Caetano São Bento

Cobra mordeu Caetano São Bento [Arthur Ramos. O negro brasileiro 1º v. - Etnologia religiosa (1940, primeira edição 1934)]2) Êh, Cauan!

Olh’a cobra, Cauan!

Êh, Cauan!

Peg’a cobra, Cauan!

Êh, Cauan!

Quem me pega essa bicha, Cauan! [Edison Carneiro, 1936. Religiões Negras]Commentary: According to Carneiro, the song is for Saint Benedict, the Saint of Snakes. Cauan, or rather, acauã, is a Brazilian falcon that hunts mainly snakes.

3) Prepare the wire - Edson Show

Ê Prepara o arame

Enverga a madeira de Jequitibá

Trás a moeda, cabaça e o caxixi da feira

Que eu quero tocar:,: Meu Berimbau, ê, ê

Meu berimbau camará

Ele é enfeitado

Com laços de fitas

E as conchas do mar :,:Eu encanto sereno

Disfarço o veneno

Venço a solidão

Rezo o S ã o B e n t o G r a n d e

S ã o B e n t o P e q u e n o conforme a razão

Na roda o medo não fala

Moleque aprende a lição

Coragem nunca se cala

Vence quem tem coração

Com os pés na senzala

Negro se ajoelha fazendo oraçãoVem menino vem

Descendo a ladeira

No cais dourado vai ter capoeira pra matar

Dança morena faceira

Vadeia na beira do mar

Negro velho de zonzeira

Vai da gameleira

Chegou pra jogar sourceComment: Bento Grande and Pequeno appear again, difficult to identify beyond the rhythms of the berimbau.

4) This is good - Xisto Baiano (1902, first song recorded in Brazil)

[..]

Oh São Bento, buraco velho tem cobra dentro!

[..]Commentary: Being on the first song recorded in Brazil says a lot about the prestige of São Bento.

4.8 Songs mentioning Omolu

1) Sons of Ghandi - Gilberto Gil

Omolu, Ogum, Oxum, Oxumaré

Todo o pessoal

Manda descer pra ver

:,: Filhos de Gandhi :,:

[..]Commentary: Omolu is an important deity in Candomblé.

4.9 Songs of Saint Benedict

1) Um dia São Benedito me disse

Que eu ia aprender a jogar

A jogar capoeira de Angola

E jogo de dentro ia me ensirar [CD by M Jogo de Dentro, 2007]2) São Benedito Está Contente (Street March)

3) São Benedito Ele Pá Nois Tá Olhano (Entrada)

4) Lá Está São Benedito (Volta da Entrada) [Folklore Records – Documento Sonoro do Folclore Brasileiro – Vol.3, 1988]

Comment: These are some songs by São Benedito to compare with São Bento. Fortunately, there aren't many and most are from the jongo dance, so there's not much confusion.

Speaking of percentages, most of the songs are definitely about asking Saint Benedict for protection. Protection is mainly sought from snakes, which are associated with capoeira players through totemism.

São Bento is also mentioned as a capoeira rhythm, less often as a capoeira game.

The songs sometimes tell how São Bento calls us, probably to his bosom, where we are protected.

The oldest songs that mention São Bento are known from the beginning of the 20th century, but probably go back much further.

Samba, jongo, coco and other Brazilian dance forms have little or no influence from São Bento.

I will try to give a possible explanation for the formation of the different figures of São Bento Pequeno and São Bento Grande as a saint and the rhythms of the berimbau of the same name in chapter 6. -

+

CHAPTER 5 - Medal of Saint Benedict and the Dobrão

5.1 The São Bento medallion

The São Bento medallion represents a single “lucky charm” or sacrament – a visible proof of faith.The front of the medallion (Image 14) represents Saint Benedict with a book in one hand and a cross in the other. In addition, to the left of the saint is a cup of poison with a crack, from which a snake comes out, and to the right is a crow flying with poisoned bread. Above these figures is the text:

CRUX S PATRIS BENEDICTI - Holy Cross of Saint Benedict

On the edge of the medallion is a circular Latin inscription:

EIUS IN OBITU NRO PRÆSENTIA MUNIAMUR - We are protected by you at the hour of our deathUnder Saint Benedict, however, the text:

EX SM CASINO MDCCCLXXX - (from) the Sacred Monastery of Monte Cassino in 1880 or simply M. Cassino, indicating that the medallion in its present form was minted there in Italy in 1880.

Image 14. Front of the São Bento medallion. Photo from internet At the top of the back of the medallion (Image 18) is the word PAX - Peace and in the middle a sign of the cross with the letters above and to the side:

C S P B (next to the cross inside the circles): Crux Sancti Patris Benedicti - Holy Cross of Saint Benedict

C S S M L (top to bottom): Crux Sacra Sit Mihi Lux - Holy Cross Be My Light

N D S M D (from left to right): Non Draco Sit Mihi Dux - Don't Let the Serpent Dragon Be My Guide

V R S (around the edge, starting from the top right corner): Vade Retro, Satana! – Get away, Satan!

N S M V: Nunquam Suade Mihi Vana - Do not lead my soul into temptation

S M Q L: Sunt Mala Quae Libas - What you offer me is bad

I V B: Ipse Venena Bibas source - Drink your own poisonThe exact origin of the locket is unknown, but it is known that the image on its back was rediscovered in 1647 at Metten Abbey in Bavaria, Germany, over which witches somehow failed to seize power. It turned out that the cause of the witches' incapacitation was the images of crosses painted on the walls of a room, with the same magical stars around them. However, its meaning only became clear later, when a manuscript written in 1415 was found in the library of the same monastery, in which there was an image of Saint Benedict and verses from his staff and pennant superimposed on abbreviations of letters. The same image is also depicted in Bernard Pez's 1721 book Thesaurus Anecdatorum Novissimus (Image 15). Later, a manuscript from 1340/50 was also found, which conveyed a similar text.

Image 15. Image deciphering the characters on the São Bento medallion. Picture from the book Then, in the 17th century, medallions with the corresponding text began to be minted in Germany (Image 16).

Image 16. Front drawing of the São Bento medallion. Photo from internet At the end of the 18th century, the medallion took on a new shape, and then changed even more (Image 17).

Image 17. São Bento medallion, late 19th century. XVIII. 40 real coin, early 19th century. Photos from the internet Having hoped to find a modern medallion on trips to France and Italy, I found a souvenir shop near the Vatican where, at my request, medallions in the right size (Image 18, because they are also made smaller, to to wear around the neck) were brought up from storage. I had to visit the same store the next day as the locket was a bit faulty - the Retro 'R' looked more like a 'P'.

Image 18. Reverse of the São Bento medallion. Private collection photos from the internet I had my two medallions blessed by a Brazilian priest in a church called San Benedetto in Piscinula (Image 10). The priest happened to be from the São Paulo monastery I mentioned above. To bless, he recited a prayer in Portuguese and sprinkled the medallions with holy water.

On the wall of a room in the church of San Benedetto in Piscinula in Rome (Image 19) there is even more interesting information about the medallion of Saint Benedict and the translation from Italian goes something like this:

[..] From these two episodes [with the poisoned cup and the poisoned bread] (but we don't know when) the devotion to the medallion of the cross of São Bento was born.

It became popular around 1050 after the miraculous healing of young Bruno, son of Hugo, count of Eginsheim in Alsace. According to some, Bruno recovered from a serious weakness after receiving the São Bento medallion. After his recovery, he became a Benedictine monk and later Pope Leo IX Font , who died in 1054.

Vicente de Paulo source must also be mentioned among the medallion distributors.

Pope Benedict XIV approved the medallion in his decree of 1742, promising the forgiveness of sins to those who wear it with devotion.

Many people who use it have received spiritual and bodily grace.

Image 19. Information on the wall of São Benedito's room. Private collection 5.2 Use of the Medallion and Coins

The oldest writing about a single wire and gourd instrument in Brazil probably comes from Henry Koster in 1816:

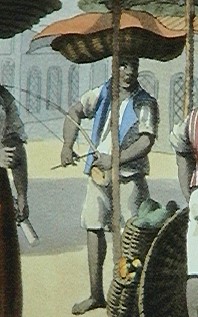

The slaves also asked permission to dance; their musical instruments are very robust: one of them is a kind of drum, consisting of a sheepskin stretched over the trunk of a hollow piece of wood; and the other is a large single-tongued bow with half a coconut shell or a small gourd tied to it. It is placed against the stomach and the wire is struck with a finger or a small wooden stick.The first writings on the use of a single-stringed percussion instrument in Brazil are by Chamberlain in 1822 (Image 20): [marimba lungungo, the African berimbau] The way of playing is very simple. The thread, duly stretched, is played gently, producing a note that is modulated by the fingers of the other hand, pinching the thread in different places, wherever they want.

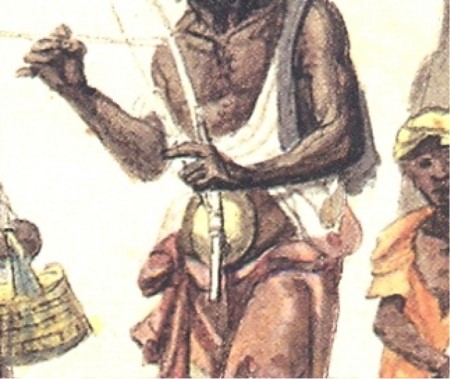

Image 20. Fragment of the image A market stall. Chamberlain, Brazil, 1822. Image from the Internet Shaffer (1977), an ethnomusicologist of the berimbau, refers to the fact that the works of Debret (Image 21) and Rugendas [none of Rugendas' photos actually showed a berimbau being played] portray the execution of the berimbau, where the fingers are used to change musical notes [the same can be seen in several images of African instruments similar to the berimbau, for example, in Image 21]. In the 19th century, however, capoeiristas also used coins, "dobrão" (40 reals, image 23) and vintém (20 reals, image 24), in place of fingers.

Image 21. Fragment of the photo Berimbau player. Debret, Brazil, 1826. Image from the Internet

Image 22. African berimbau. Photo from internet

Image 23. 40 reals. Photo from internet

Image 24. 20 reals. Photo from internet The copper plates in use today are called "doubloons" based on these notes, but Shaffer's analysis (1977) points to the fact that the use of doubloons was only real from the 19th century, when the 40 reals had already lost its exchange value [40 and 20 reals were in use until 1912]. In the 19th century, this amount was considerable, and black berimbau players, especially slaves, did not have access to it, at least not for such purposes. On the other hand, at the beginning of the 20th century, the use of this currency became a status symbol for capoeiristas. [Dobrão] is an object that has had a magical aura since the beginnings of the use of the berimbau in capoeira. The 40 real doubloon and the São Bento medallion were both copper [or bronze] and had the same 25 mm diameter as many doubloons used by angoleiros today.

De Brito (2011) believes that after the use of fingers and before the introduction of the dobrão, there was a time when the São Bento medallion was used to play the berimbau, and by metonymy [name change, renaming] the berimbau rhythms came to be called São Bento because they were literally interpreted through the symbolic figure of São Bento. Here we see an almost completely forgotten syncretism [...].

5.2.1 Examples of medallion use in the 20th-21st centuries.

[..] Mestre Bimba created an evaluation test where the novice should receive the medallion of São Bento, which was placed on his chest, after completing the course. If he could do that, he would graduate too. Note: The medallion could only be picked up with the feet. When the novice, already formed, succeeded, he went to meet the capoeira godfather to ask for his blessing. Then an advanced capoeirista gave him a “blessing” [direct kick in capoeira Regional] in the chest, pushing him down and saying: Now you are baptized. And gave him his first rope [used in place of the sash in capoeira Regional] source .The image on the back of the medallion of São Bento was used in a modified form in the logo of the capoeira group São Bento Pequeno source created in 1995 (Image 25). Compared to the original, the medallion has changed the letters inside the circles next to the cross.

Image 25. The Grupo São Bento Pequeno logo. Photo from internet [..] For devotees, [the medallion] is a remedy against physical and mental ills, originating from both humans and animals. In addition to carrying it, it is customary to bury it in the foundation of houses that are being built, so that those who live there can benefit from source .

-

+

CHAPTER 6 - The rhythms of São Bento and the berimbau

It is clear that the fusion that already occurred in other areas of Brazilian life also began to occur among capoeiristas, for example, many capoeiristas drew the name of the Father (the sign of the cross), a Catholic symbol, before playing. Some berimbau rhythms were named after Catholic saints such as São Bento, Santa Maria, and also in many songs we can observe such syncretism, unification source .

I list below the references I found to various berimbau rhythms that contain the name of São Bento.

1) São Bento Pequeno – common name; see also Shaffer, 1977

2) São Bento Pequeno from Angola source – unusual name; probably the same as #1

3) São Bento Grande de Angola - common name, for example, on the CD L'Art du Berimbau, 2001

4) São Bento Grande Repicado - M Dorado (mouth to mouth); looks like #3

5) São Bento de Angola - M Mendonça tape K7; probably the same as #3

6) São Bento Grande de Bimba – common name

7) São Bento Grande de Regional - common name, for example on the CD L'Art du Berimbau; same as number 6

8) São Bento Repicado – Shaffer, 1977; M Mendonça K7 tape; remember number 6

9) São Bento Dobrado – Shaffer, 1977; resembles number 6

10) São Bento Grande de Compasso - M Gato Preto on the CD L'Art du Berimbau; M Black Cat (Shaffer, 1977)

11) São Bento Grande in Gêge - M Canjiquinha (Shaffer, 1977)

12) São Bento de Gêge - to glorify the orixá Oxumaré (Rego, 1968); probably the same as #11

13) São Bento Amarrado – another name for the rhythm Angola, interview by M Meinha source ; M Mendonça K7 tape

14) São Bento Preso - another name for the rhythm of Angola, according to M Pelicano

15) São Bento Grande de Santo Amaro - M Gato Preto on the CD L'art du Berimbau; M Gato Preto on the CD Ass. de Liberdade, 1999

16) São Bento de Dentro - M Gato Preto (Shaffer, 1977); According to M Gato Góes (son of M Gato Preto) this could be another name for São Bento Grande de Santo Amaro source (probably same as #14)

17) Amazonas with sound of São Bento - Shaffer, 1977Furthermore, Arnol (Shaffer, 1977) names the mysterious São Bento without suffix as one of the rhythms.

Usually rhythms with "em gege", "repicado", "doubled" or some other variation of the simple name are variations of this rhythm. [Shaffer, 1977]

With this in mind, probably counting the same and the similar rhythms as one and removing the numbers 13 and 16 as non-São Bento rhythms, I get a total of 5 rhythms. I divide them into two groups below and point out the most common way to play:

I The most common rhythms of São Bento:

1) São Bento Pequeno - chi chi tin ton [trebbling, high and low sounds]

2) São Bento Grande de Angola - chi chi tin ton

3) São Bento Grande de Bimba - chi chi ton ton tinII From the line of M Gato Preto come the rhythms of São Bento, which actually sound more like variations of São Bento Grande than independent basic rhythms:

4) São Bento Grande de Compasso - chi chi tin chi tin ton

5) São Bento Grande de Santo Amaro - ton ton (ton) tin tonIn conclusion, 3 rhythms from São Bento remain: Pequeno, Grande de Angola and Grande de Bimba. However, we can also take from them the self-titled rhythm of M Bimba, as this master became known as a mixer and style changer, and the order of the beats of the rhythm does not correspond to the obvious order of highest note (tin) to lowest (ton ) in São Bento.

How did capoeiristas use São Bento so much? To simplify again, there are 2 groups of basic rhythms played on the berimbau: one has the sequence of notes from the lowest to the highest (ton-tin) and the other is the opposite (tin-ton). The first probably came to be called the Angolan rhythm to refer to the African nation of the same name, where most capoeira slaves came from, while the second group may have been called São Bento after the Catholic saint who protected the slaves. Angolan slaves. The two most common rhythms of São Bento, however, began to refer to the two figures of São Bento - the Small (Pequeno) and the Great (Grande). However, this version can be questioned, as in that case it would be more likely to use the Yound (Novo) and Old (Velho) suffixes.

According to a possible explanation for the formation of the names of the rhythms, it is very likely that the approach of the rodas to the celebrations in Largo das Igrejas has led to I'm not just to "praise the Lord!" and the inclusion of litanies, but also the creation of rhythms:

São Bento Grande, São Bento Pequeno, Angola and Santa Maria - influenced by the sound of church bells!

Ton-tin: Angola

Tin-ton: São Bento Pequeno

Tin-ton-ton: São Bento Grande sourceIn his 1932 book Rio de Janeiro Durante os Vice-Reis, Edmundo tells how the bells of the 18th-century churches in Rio de Janeiro, including the Church of São Bento, made noise all the time and sounded as if were talking to each other.

A connection with African gunga bells [Gunga – ngunga = bell in Kimbundu. Calunga and the Legacy of African Language in Brazil] is also possible (Image 26). Gunga is known as the name of the largest or medium berimbau in capoeira.

Image 26. Gunga bells. Photo from the internet With great difficulty I found a reference that offers another possible solution to the question of Saint Benedict, the Little [Pequeno] and the Great [Grande]. Namely, there was a church called São Bento, built in the 17th century and abandoned around 40 years ago. This church was a kind of aid base for the Benedictine monks who traveled through Pernambuco and Alagoa on their missions in the 18th century. From the church, now in ruins, several objects of value related to the saints were stolen, among others the icon of the patron saint São Bento “pequeno”, of which only a framed image survives source (Image 27). Unfortunately, there are no more sources that confirm the version that it was this saint with a young and bloody face who provoked the later introduction of São Bento Pequeno and, on the other hand, São Bento Grande as names for instrumental rhythms.

Image 27. “Small” Saint Benedict. Photo from the internet Finally, São Bento Pequeno can also be derived from São Bento Infantil (Image 28). There seem to be child-saint versions of most or even all saints, the most famous of which is the Christ Child.

Image 28. Infant Saint Benedict with cup and crow. Photo from the internet -

+

Summary

Capoeira has always been considered an activity influenced by several continents. It is difficult to assess the size of the influence of one or another part of the world on the final product - there are capoeiristas who consider capoeira a subculture of 50% African and 50% Brazilian origin, others who think that the percentages are skewed towards the mother-daughter side and others that also see Brazilian and Portuguese indigenous influences.

To this last understanding we can safely add the influence of the Catholic Church, which, along with the set of religions of African origin, gave capoeira its modern form. In their songs and prayers, capoeiristas turn to Candomblé and to God and Catholic saints. Recently, evangelists have begun to suppress African influences in capoeira, but their influence is quite marginal.

São Bento has a role of its own in this entire community – even greater than it seems at first sight. São Bento is a phenomenon of its own in capoeira, without him it is impossible to imagine the pastime of slaves. If someone came up with a plan to rid poultry of Catholic influences, it would be no less bad than the evangelists and their Christian intentions.

Although São Bento came from Italy, his legacy belongs to the world and, through the Benedictine monks, capoeira also became part of it. So much so that he is the best-known saint to whom songs turn when seeking protection in the circles. Choosing a holiday is not random, of course, but a manifestation of a modern version of a centuries-old tradition.

The slaves brought to Brazil received spiritual and spiritual help from the hands of Saint Benedict, although we must admit that Christianity is the slaveholders' religion in this equation, and the Catholic saint only replaced the existing African deity. However, such substitution or syncretization seems to be very viable and, although a large part of Afro-Brazilian culture has tried to remain or return to its religion, it is still not possible in its previous form, at least in the case of capoeira. São Bento came to stay.

The origins, deeds and beliefs of São Bento are probably not in the daily thinking of capoeiristas, at least not in the same way as the former deceased mestres: Pastinha, Bimba, Waldemar et al. This is because São Bento's connection with capoeira is not so obvious and knowledge of São Bento is obscured by the veil of history. Much knowledge about the old masters is also disappearing, while much material is lacking about the development of capoeira before the end of the 19th century. So we couldn't find solid evidence about capoeira and São Bento, we can only make good or bad guesses. I can only hope that there is more news in this work and that the mystery of São Bento has been unraveled a little.